a red disk swimming in a blue sea

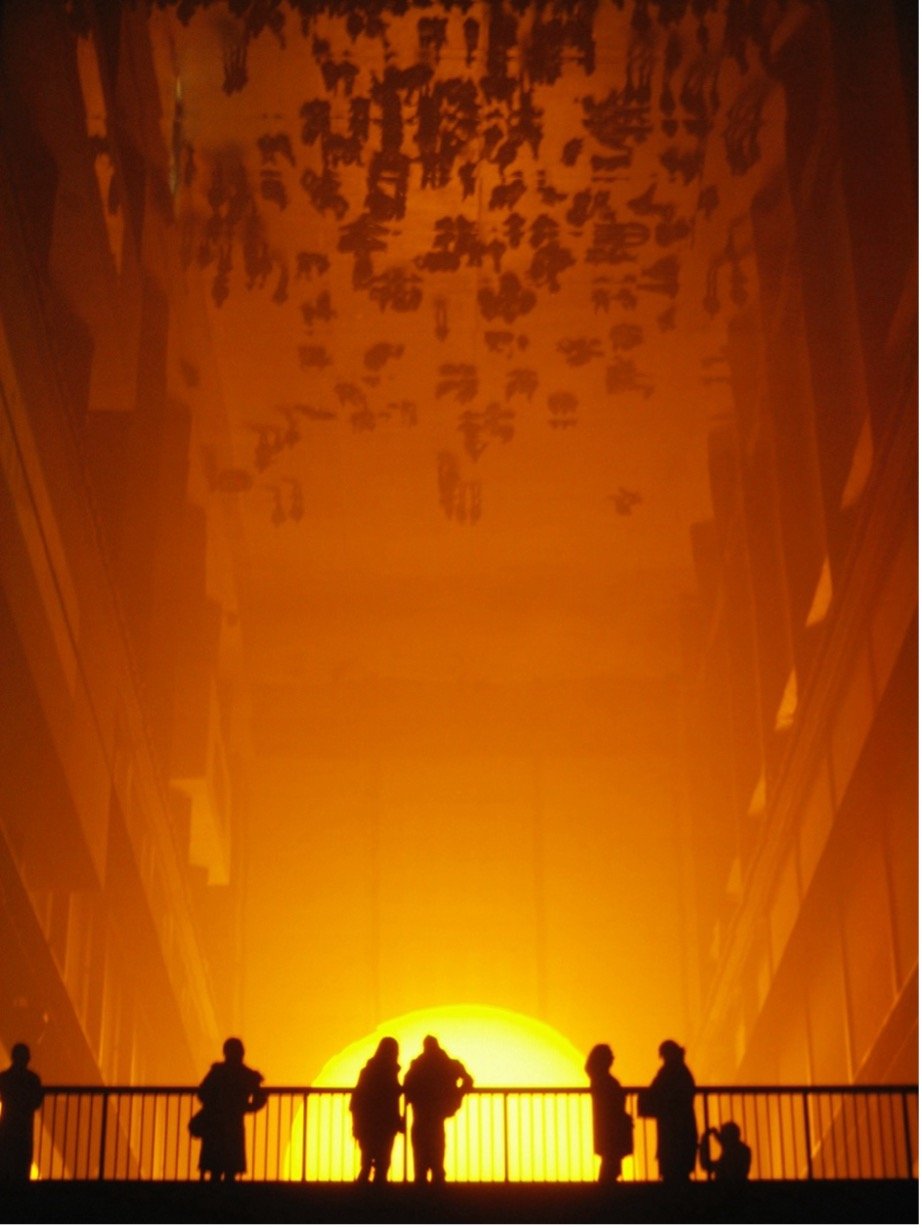

It’s October 16, 2003— a Thursday in London, and the sunlight has lingered long beyond its usual daytime hours, but the evening breeze is slight, maybe not here at all, and the warmth isn’t coming from the solar disk but from accumulating body heat in the confines of an enclosed, industrial space. Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project has transformed the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern into an ethereal, artificial sunscape. A culmination of millennia of ancient worship and arcane wonder, of the sun’s sublime beauty and that temporary wash of sunset’s orange glow suspended for moment after moment in time.

A semi-circular light fixture is suspended from the Turbine Hall’s ceiling, a ceiling plated with mirrors from beginning to end. It’s a craft perfected by amateur and prolific magicians alike; using a mirror to double and expand an image to create the illusion of endlessness, to make something appear floating or otherworldly. Eliasson’s semi-circular disk is doubled just the same, made to appear as a complete circle, a complete solar disk.

As we look up, we look down. Our silhouettes reflected in the ceiling, staring down to earth. It seems there’s a threshold where our half of the sun ends, and theirs begins, and perhaps that transition from reality to reflection also enacts a reversal, and their solar disk is not a solar disk at all, but emblematic of something else. It might be the case that it’s October 16, 2003, a Thursday in a parallel London, and the reflection of the semi-circle is not a solar disk but something deeper, bloodier, a rusted hue. The Weather Project might instead be emblematic of the planet Mars.

*

For centuries, the red planet – the planet Mars – has been an accessory to celestial fears and mortal lament. Its blood-red hue abets the identity of an antagonistic, war-torn infernal underworld. But in the far, far future, it seems that human migration is headed straight towards this place that has long been associated with misery, battle, and rage. Why would we set sail for a planet that has, for so long, haunted ancient mythologies with threats of a torturous afterlife?

Here's our situation: by estimates, the next few centuries of climate change will pose a significant threat to humanity. Our swollen sun is forecast to swallow the oceans one-billion years from now, leaving nothing behind but a cavernous terrain unfit to sustain life.

Our sun, no stranger to contradiction, has perhaps long harboured both divine and destructive roles. The sun discerns time, direction, religion and reason. But it also governs the limits on our days, years, months, it governs what burns and it governs what doesn’t, what melts, what grows, what perishes, what goes. The sun is a paradoxical emblem of beginning and of end, of sustenance and destruction simultaneously, something for centuries we imagined ascending to, something we’re unable to look at directly. There have always been two suns. One of blinding beauty, and one that blinds.[1] Its poetic gesture is so easily overturned with nothing but heat. The sun, on a path to decay, is set to destroy Earth, and we might find ourselves in search of a new planet to call home.

*

Our only condition of entry to Mars is to let go of the fears that have guided us, so far, to safety in numbers on Earth. And we’re well on our way to that letting go. In time, it seems that the archaic perspectives of the Sun and Mars as symbols of life and of death, respectively, have swapped, have usurped each other’s identities.

There’s a moment in recent history, the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where humanity succumbed to a dire case of Mars Fever. Everyone’s afflicted. With anything red and burning a suitable host for fear, collective earthly concerns were piled up and projected onto the red planet; a result of rapid technological and telescopic advancements which revealed dark markings and polar ice caps across the surface of Mars.[2]

Canals. Evidence of water. Evidence of past life, of intelligent life, even. Suddenly humanity’s fear of war has shifted from neighbouring countries to neighbouring planets, and the collective consciousness is plagued by more than the worst humankind has to offer; the focus instead is on Mars. A hostile site home to unbridled fear, and worse— apparently, it’s inhabited. Apparently, it’s alive.

*

Seeing is believing. It’s a condition of fearing Mars that one must subscribe to an irrational belief forged by millennia of myth and unfounded anecdotal speculation, and though I’ve never met a Martian, Helene Smith has. In hallucinations, visions, trances – wherever it is that mediums go – and she sees them all the time. They taught her a Martian script and showed her Martian landscapes and the Martian way of life. In astral projections she held pencils and transcribed what the Martians would write to her. “How much I regret your not having been born in our world,” the Martians had said, “you would be much happier there, since everything is so much better with us, people as well as things, and I would be happy to have you near me.”[3]

It's hard not to believe in a written script, in a spectral conversation made tangible. Regardless of legibility or access, we are so liable to accept that a transmission of information has taken place, that any information transcribed has a credence or credibility.

Believing, then, is also involuntary. It’s October 30th, 1938. The evening’s radio program of dance music has been interrupted by a bulletin from the Intercontinental Radio news:

“At twenty minutes before eight, central time, Professor Farrell reports observing several explosions of incandescent gas, occurring at regular intervals on the planet Mars. They’re moving towards Earth with enormous velocity. Like a jet of blue flame shot from a gun.”4 The radio host asks the professor to tell the audience exactly what he sees, as he observes the planet Mars through his telescope.

“Nothing unusual at the moment,” he says, “A red disk swimming in a blue sea. Transverse stripes across the disk.”

Nearer to 8:50pm, the radio reports a large, flaming object – akin to a meteorite – that has catapulted into a nearby farm. The professor notes a metal casing, and it’s definitely extraterrestrial, he says, not found on this earth. And something’s happening, he says. The top is rotating, like a screw, and there is something inside trying to escape.

The next morning, the headline of the Boston Daily Globe Newspaper reads:

RADIO PLAY TERRIFIES NATION

Mars Invasion Thought Real

Hysteria Grips Folk Listening In Late

Many Fear World Coming To End [5]

As you do, when you’re a playwright and it’s the evening before Halloween, Orson Welles had performed a Halloween Special radio adaptation of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. Needless to say, with the fear of Mars at that time aggravated by an onset of Mars Fever and a harsh over-consumption of science fiction, rapid technological advancement, and a steadily increasing distrust of the stability of Earth as a long-time sustainable home, it was easy to amass a collective belief in any fictional narrative centred on the misgivings of the red planet. But the let-down the next morning, the announcement that it was all a hoax, swept the news and media in a swift wave that softened centuries of Mars’ poetic past as a fearsome underworld.

And besides. There was evidence of past life. Maybe there’s possibility for human survival.

*

So people still dreamed of stars, of Mars, as they recuperated in recovery rooms from the fever of the red planet. Thoughts of travelling to Mars – that is, sending humans to Mars – really began circulating in the late 1940s, no more than ten years after Orson Welles’ stunt on the radio. It was less than fifteen years after that that the Mariner 4 spacecraft became humanity’s first cold-call knock-and-run of the red planet, taking the first close-up images of its surface to reveal a barren and cratered world. A projected mirror reflection of Earth in some billion years from now. There’s no life here.

Here, perhaps, is where our perception of the planet of war truly disseminated. Any lingering fears of its bloodlust had, for the most part, subsided.

But it’s interesting— regardless of scientific advancement, Mars has never strayed from a place we imagine life to end up; even if that life were the otherworldly kind, the underworldly, the kind you encounter after Earth, after human expiry, after whatever grand reckoning awaits us. Mars has remained the next destination. Only its poetic status, as one of untimely demise and eternal torture, has self-amended from a wasteland of human souls to a place of refuge.

*

But our pursuit of Mars feels terribly anthropocentric, self-serving. There is a homesickness wrought deep in our genetic makeup, something that points us, as tourists, migrants, towards Mars. To carry out that interplanetary exploration, to search for something else that could be grappled with, and settled on, as a new kind of home.

There’s a rumour, a theory with significant scientific backing, that Earth was born a twin. [6] Theia was her name. She was, by all accounts, roughly the size and likeness of Mars, but in the first 40 million years of their nascent lives, Earth and Theia were helpless in delaying or preventing their imminent collision. The force of gravity grew beyond comprehensions, and they pulled each other off course.

It was one or the other.

Theia shattered to pieces.

Some pieces scattered into the atmosphere, gone, ashes, spread and remembered, an interplanetary family portrait that never quite made the mantlepiece. Other pieces, less conducive to the gravitational pressure, stayed fairly in-tact. One of those pieces became the Moon. The other impaled the crust of the Earth. Conjoined twins, in a way.

Earth’s collision with Theia is what enabled it to grow large enough to sustain an atmosphere— to sustain life.

*

It’s four-and-a-half billion years after – 1969 – and the Moon has become the first human-led interplanetary undertaking. A mere few years after the Mariner 4 was sent on an imaging mission to Mars. Our first human pursuit of some other world, some impossible concept made tangible. To walk on another planet. To walk on the remains of one.

Maybe Theia is embedded in an Earthly unconsciousness, some born desire that we acquire as inhabitants of this place. Re-uniting with our galactic twin perhaps forged into some spectral navigation compass, forever pointing us to anything which evokes her likeness. To piece together some kind of family portrait that we were unable to collect scraps for prior to her sacrifice. A memorial, a shrine.

There’s a Derridean theory in Archive Fever that says we mindlessly chase the past to chase our own origins. A nostalgia, he calls it. “This painful desire for a return to the authentic and singular origin… it is to burn with a passion, it is never to rest, interminably, from searching for the archive right where it slips away.”[7] And Mars, as a facsimile of sorts of this mythologised Theia, is exactly that. That slipping presence, that arcane origin story that is visible enough to chase but too fleeting and intangible to grasp. “It is to have a compulsive, repetitive, and nostalgic desire for the archive,” Derrida continues, “an irresponsible desire to return to the origin, a homesickness, a nostalgia for the return to the most archaic place of absolute commencement.” Our pursuit of Mars is fuelled by an arcane, nostalgic impulse to be with the likeness of a martyred sibling planet.

*

It's some decades from now, centuries, perhaps. The desert sands beneath our feet are dry and red, and we walk through a timeless space, where it’s colder, dimmer, and from the Martian horizon we gaze at our old planet Earth, a place that recalls a mass exodus from the years prior to now.

Some years ago, in 2019, a reddit user took to the internet with two images of two sunsets. One, a burning red-orange as we see in Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project. The other of a cold, blue, desaturated atmosphere. The reddit user’s caption reads: ‘View of Sun from Earth left, Mars right. I think Sun on right is too depressing. I follow up with my views on how to solve depressing Sun problem on Mars.’ [8]

A direct quote from their brainstorm of solutions reads, “put nuclear power plants in an artificial ship-moon-thing that orbits around Mars with approximate placement in the sky of Mars as the sun is, that is full of light bulbs directing their light down at Mars.”

To clarity— the reddit user suggests we make a grand Olafur Eliasson Weather Project in the atmosphere of Mars. An artificial sun. Smoke and mirrors.

So maybe the sun’s poetic symbolism hasn’t devolved, only become dimmer, and we’ve instead chosen to put more physical distance between ourselves and that solar disk by means of self-preservation, so we can continue to look at it, perhaps even directly, free from harm. The solar disk has, it seems, never ceased to amaze, to amass wonder, only in time we have learned our lesson and we travel away from it rather than towards. As the distance between us and the swelling sun expands, we fuel and refuel this refusal to accept that such sublime beauty should ever be the cause of our extinction. And that no matter the circumstance, the sun might remain in a poetic state of reverie and reverence. An emblem not of our end, but of our evolution.

So it’s a Thursday in October, 2003, back in London, back on Earth, in that parallel mirrored ceiling of instability and ambiguity. There are people inside the Turbine Hall, at the Tate Modern, where Olafur Eliasson has constructed a large, glowing disk – smoke and mirrors – a monument to a lost sibling planet, to Theia, a family photograph on the mantlepiece, a compass, a map pasted to the front windscreen of the car, the direction we’re headed.

Published in print and online in ‘Refuse,’ issue no. 42 of Framework

Read/Performed at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 6 November 2024

____________

Notes:

1. In his 1930 text ‘Rotten Sun’, Georges Bataille says of the sun’s dualistic nature, “the sun has also been mythologically expressed by a man slashing his own throat, as well as by an anthropomorphic being deprived of a head… the myth of Icarus is particularly expressive from this point of view: it clearly splits the sun in two— the one that was shining the at the moment of Icarus’ elevation, and the one that melted the wax, causing failure and a screaming fall when Icarus got too close.” See Georges Bataille, ‘Rotten Sun,’ in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939, ed. and trans. Allan Stoekl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 57-59.

2. ‘Canals’ on Mars were first observed in 1877 by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, which he described as ‘canali’, meaning channels or grooves, which was later misinterpreted in English as ‘canals’, which suggests artificial waterways constructed by intelligent life. Original citation: Giovanni Schiaparelli, Osservazione astronomiche e fisiche sull’asse di rotazione e sulla topografia del pianeta Marte (Milan: Tipografia dei Fratelli Rechiedei, 1878).

3. Théodore Flournoy, From India to the Planet Mars, trans. Daniel B. Vermilye (1900), http://www.sacred-texts.com

4. Orson Welles, The War of the Worlds Invasion from Mars): Radio Script from Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre. https://www.erbzine.com/mag23/War_of_the_Worlds.html

5. The Boston Daily Globe, Monday Morning, October 31, 1938.

6. Paul Sutherland, ‘Theia Slammed into Earth, Left Marks, and Then Formed The Moon, Study Suggests.’ Astronomy, September 25, 2023. https://www.astronomy.com/science/theia-slammed-into-earth-left-marks-and-then-formed-the-moon-study-suggests/

7. Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Translated by Eric Prenowitz. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

8. u/Bwa_aptos, r/Colonizemars, ‘View of Sun from Earth left, Mars right. I think Sun on right is too depressing. I followup with my views on how to solve depressing Sun problem on mars.’ Reddit, 2019. https://www.reddit.com/r/Colonizemars/comments/de5tnc/view_of_sun_from_earth_left_mars_right_i_think/

Images:

Olafur Eliasson, The Weather Project, Exhibition. London: Tate Modern, 2003-2004.